The Role of Engagement and Presence in Online Courses

Engagement

is related to motivation, in this instance the motivation to stay engaged in

online courses. Maslow (1943, 1954, 1970) suggests that people are motivated to

meet certain needs. When one fulfills a need, the person moves on to fulfill

the next one. His earliest version of this

hierarchy of needs included

five motivational needs, often depicted within a pyramid (see Figure to the right).

These first four needs are identified as

deficit needs. If these

deficit needs are not met, these needs make us uncomfortable, motivating us to

sufficiently fulfill these needs. Referred to as

growth needs, the last

four needs constantly motivate us as they relate to our growth and development.

Maslow

also arranged these needs in a hierarchy, indicating that we are primarily

motivated by a need

only if lower level needs have been met. This means

that before cognitive or self-actualization needs can motivate us, we must

address the basic deficit needs like physiological, security, belonging, and

esteem. After students meet level 1basic needs and the safety needs of

level 2, they next strive to meet the belonging needs of level 3. This level

involves emotionally-based relationships in general, such as friendship,

intimacy and having a supportive and communicative family. Students who lack

these close relationships often exhibit low initiative and low levels of

extraversion, impacting their ability and interest in interacting. Faculty can

assist here by creating opportunities for students to interact with one another

and with faculty, in a gamified environment, by using technology to foster

community, one where students feel they belong. Faculty, then, can begin

developing engagement by meeting students at their level 3 needs and continuing

up through the levels.

Gamifying a class may be one way to help meet these

needs.

A

sense of community, also a part of engagement, has been significantly linked to

perceived learning (Rovai, 2002; Shae, 2006). Garrison (2007) refers to

community as presence, comprised of three types: social, cognitive, and

teaching presence. Garrison, Anderson, and Archer (2000) developed a

comprehensive Community of Inquiry framework (see Figure on the left) that suggests

developing a community of learners is crucial to supporting higher level

learning and discussion.

Research suggests this

framework provides solutions for studying online learning (Garrison &

Archer, 2003; Garrison,

Cleveland-Innes, Koole, & Kappelman, 2006). Garrison et al. (2000) argue

that any one of cognitive processing, social interactions, or teachers’

facilitation by itself is insufficient for fostering higher levels of critical

thinking, but instead, these three elements have to co-exist and interact with

one another to optimally facilitate learning (Bangert, 2008).

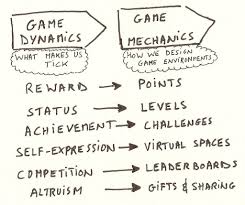

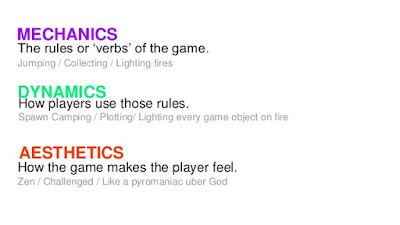

Aligning the

integration of gamification into online courses using the MDA Framework and the

Community of Inquiry Framework seems to be an appropriate place to begin.

Social presence

Students demonstrate

social presence when they project themselves as real people within a community,

establishing personal and purposeful relationships. A key point here is for students to recognize

they are not here purely for social reasons, but to interact with common

purpose for the sake of inquiry. Students need to feel secure to communicate

openly and to create cohesion. Swan and Shih (2005) found that group cohesion

is significantly related to social presence and perceived learning outcomes.

Richardson and Swan (2003) go on to connect social presence with student and

instructor satisfaction with and perceptions of a course. Social presence in

online discussions has even been identified as a predictor of academic

performance and can be used as early detection for students at risk of failing

an online course (Joksimovic, Gasevic, Kovanovic, Riecke, & Hatala, 2015).

Teaching presence

Teaching

presence relates to the process of design, facilitation, and direction

throughout the learning experience to achieve desired learning outcomes. Teaching presence should directly and

indirectly facilitate social interactions and stimulate higher levels of

cognitive processing. Interaction and discourse play a key role in higher-order

learning but not without structure (design) and leadership (facilitation and

direction). For example, without explicit guidance, students will likely engage

primarily in serial monologues with brief responses rather than truly delving

into the topic presented for discussion. This may require faculty to be more

directive in their initial posts or in their responses, directing students to

solve a particular problem or to require certain elements be present in student

responses. Garrison and

Archer (2003) suggest that teaching presence is a significant determinate of

student satisfaction, perceived learning, and sense of community. Students

relate timeliness of teacher direct comments to assignments as increasing their

course satisfaction.

Cognitive presence

Cognitive presence

relates to the design and development of instructional materials, enabling

students to construct and confirm meaning through related refection and

discourse. Cognitive

presence is the degree to which the learners can construct understanding

through sustained reflection and communication (Rourke, Anderson, Garrison,

& Archer, 2001). The phases of cognitive presence (Garrison, Anderson,

& Archer, 2000), in increasing complexity, include (1) Triggering Event

(that triggers issues for consideration); (2) Exploration (of issues, through

brainstorming, questioning, and information exchange); (3) Integration (to

construct meaning based on the ideas generated in Exploration); and (4)

Resolution (to build consensus as learners confirm their understanding and apply

new ideas to solve problems).

My step, then, is to explore how to integrate the MDA Framework into the Community of Inquiry.

References

Bangert,

A. (2008, September). The influence of social presence and teaching presence on

the quality of online critical inquiry.

Journal

of Computing in Higher Education, 20(1), 34-61.

Garrison,

D. R. (2007). Online community of inquiry review: Social, cognitive, and

teaching presence issues.

Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks,

11(1), 61-72.

Garrison,

D. R. Anderson, T, & Archer, W. (2000). Critical inquiry in a text-based environment: Computer conferencing in higher

education.

The Internet and Higher

Education 2(2–3), 87–105.

Garrison, D. R., & Archer, W.

(2003). A community of inquiry framework for online learning. In M. Moore

(Ed.),

Handbook of distance education.

New York: Erlbaum.

Garrison, D. R., Cleveland-Innes, M.,

Koole, M., & Kappelman, J. (2006). Revisting methodological issues in the

analysis of transcripts: Negotiated coding and reliability.

The Internet and Higher Education, 9(1),

1–8.

Joksimovic, S., Gasevic, D., Kovanovic,

V., Riecke, B. E. & Hatala, M. (2015). Social presence in online

discussions as a process predictor of academic performance.

Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 31, 638-654.

Maslow, A. H. (1943). A theory of

human motivation.

Psychological Review, 50(4), 370-96.

Maslow, A. H. (1954).

Motivation

and personality. New York: Harper and Row.

Maslow, A. H. (1970).

Religions,

values, and peak experiences. New York: Penguin.

Richardson,

J. C., & Swan, K. (2003). Examining social presence in online courses in

relation to students’ perceived learning and satisfaction.

Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks, 7(1), 68-83.

Rovai, A. P. (2002). Sense of

community, perceived cognitive learning, and persistence in asynchronous

learning networks.

The Internet and

Higher Education 5(4), 319–332.

Shea, P. (2006). A study of

students’ sense of learning community in online environments. Journal of Asynchronous Learning

Networks 10(10). Retrieved from >http://www.sloan-c.org/publications/jaln/v10n1/v10n1_4shea_member.asp

Swan,

K. & Shih, L. F. (2005, October). On the nature and development of social

presence in online course discussions.

Journal

of Asynchronous Learning Networks 9(3).

Retrieved from http://www.sloan-c.org/publications/jaln/v9n3/pdf/