Game Design and Gamification

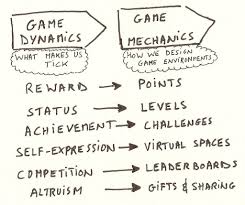

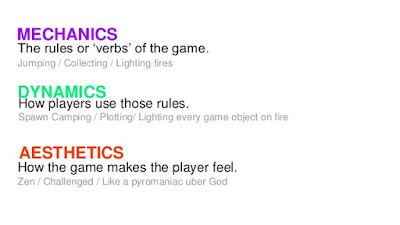

MDA (Mechanics, Dynamics, and Aesthetics) Framework provides one approach to understanding games and how gamification works (Elverdam & Aarseth, 2007; Kim, 2015; Robson, et al., 2015), breaking down games into three components from the users' perspective: rules, system, and fun. From the designer's perspective, this turns into mechanics, dynamics, and aesthetics (Kim, 2015; Robson et al., 2015). The figure below shows the progression within the framework. The flow moves from the Designer (or Instructor) with Mechanics, then moves through Dynamics, and on to Aesthetics where the player/student is, moving from the basic components to the emotional response. All three of these components are necessary to maintain engagement and change behavior.

Game mechanics

Game mechanics involve the distinct set of rules that dictate the outcome of interactions within the system. Points, badges, leader boards, statuses, levels, quests, countdowns, tasks/quest/missions, and other particular rules and rewards all fall under the category of game mechanics (Kim, 2015). Three different types of mechanics are extremely important in games and in gamified experiences: set up mechanics, rule mechanics, and progression mechanics (Robson, et al., 2015).- Set up mechanics include what shapes the environment of the experience. This includes the setting and objects and how those objects are distributed to the players. This also includes who the player is playing against - are they known or unknown? Are they internal or external? It is in this component where designers determine the spatial dimensions of the virtual world along with regulating when the experience will happen (i.e., real-time or turn-based and finite end or infinite play). Player structure is also part of game mechanics: how many can play? Is it single or multi-player? Single or multiple teams? Strangers, friends, or allies? (Elverdam & Aarseth, 2007). Although this speaks primarily to game design, set up mechanics are also important in gamifying a course. Will students play/interact individually, in one large group, or in small groups? While most instructors may not begin gamification by using a virtual world, considerations regarding amount of time available to complete a task and whether or not tasks are completed synchronously or asynchronously do need to be address.

- Rule mechanics shape the goal of the gamified experience (Elverdam & Aarseth, 2007), describing permissible actions as well as constraints that limit those actions to create pressure for the players (Kelly, 2012). If players make the same decisions each time they play, will the results be the same, or is there some element of chance? Do interactions with other players impact the outcome? Rule mechanics can also be topological or time-based. Topological includes spaces where players land - are they rewarded for landing and checking in? Time-based mechanics address whether players have to react within a specific time period and how resources build up or deplete. Objectives-based rule mechanics refers to the effects of specific circumstances, such as completing one level to unlock the next (Robson, et al., 2015). When applying this to a gamified course, instructors might consider actions such as rewarding students who “check in” or complete a task on a holiday or a weekend, those who check in daily, or those who interact with a specified number of other students within a specified time period. Embedding Easter Eggs (a hidden message, or feature, in an interactive work such as a computer program, video game or screen) within content is another example of rule mechanics as is providing students with choices in tasks.

- Progression mechanics dictate the reinforcements present in the experience (behaviors with rewarding outcomes are likely to be repeated in the future). This can be done with badges, achievement awards, levels, resources, and such. The achievements - or rewards - must be valuable to the player or the player may lose interest and stop playing. Having a balance of rewards is most desirable - after all, if everyone earns the top prize, then how much is the top prize really worth?

Mechanics form the structure for the game experience. On their own, however, mechanics are not enough to change behaviors or boost one's performance. Game dynamics and emotions or aesthetics animate the game experience and facilitate behavior change. It is this interdependence between mechanics, dynamics, and aesthetics that signals the designer what changes need to be made to the mechanics to result in behavior changes.

Game Dynamics

Game dynamics refer to the principles that create and support aesthetic experience. Unlike the game mechanics set by the designer, game dynamics describe in-game behaviors and strategic actions and interactions that emerge during play (Camerer, 2003). Examples of game dynamics include behavioral momentum, feedback, progress, time pressure, and certain abilities that game avatars can develop (Kim, 2015). Dynamics are difficult to predict and can lead to some unexpected behaviors and outcomes which can be either positive or negative. The challenges for designers, then, is to anticipate the types of dynamics that can emerge and develop the mechanics of the gaming experience accordingly.Game Aesthetics

Aesthetics encompass the various emotional goals of the game: sensation (game as sense-pleasure), fantasy (game as make-believe), narrative (game as drama), challenge (game as obstacle course), fellowship (game as social framework), discovery (game as uncharted territory), expression (game as self-discovery), and submission (game as pastime) (Kim, 2015). Aesthetics, then, are the result of how players follow the mechanics then generate the dynamics. Playing games should be fun and appealing. Assuming that players will stop playing if they do not enjoy themselves, then creating player enjoyment should be the main goal (Robson, et al., 2015).I wonder how the MDA Framework might apply to online course design.......

References

Camerer, C. (2003). Behavioral game theory: Experiments in strategic interaction. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.Elverdam, C., & Aarseth, E. (2007). Game classification and game design construction through critical analysis. Games and Culture, 2(1), 3-22.

Kelly, R. (2012). Adding game elements to your online course. OnlineCl@ssroom 14(11), 2-5.

Kim, B. (2015). Designing gamification in the right way. Library Technology Reports 51(2), 29-35.

Robson, K., Plangger, K., Kietzmann, J. H., McCarthy, I., & Pitt, P. (2015). Is it all a game? Understanding the principles of gamification. Business Horizons, 58, 411-420.

Best free local business listing website in Faridabad. These sites help your business to get huge traffic from targeted customers.

ReplyDelete